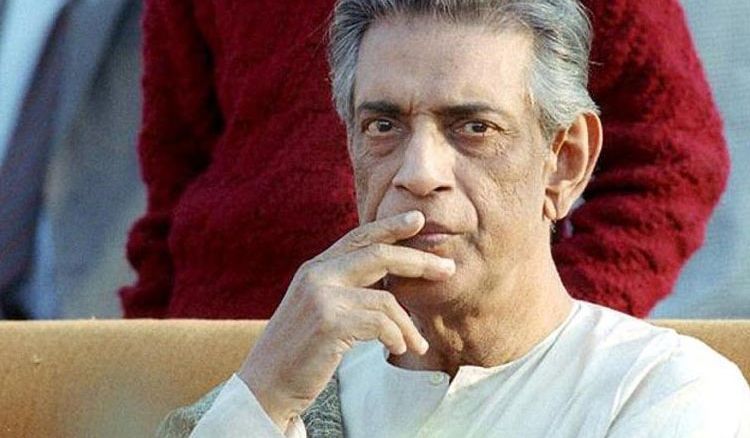

Satyajit Ray, the master storyteller, has left a cinematic heritage that belongs as much to India as to the world. His films demonstrate a remarkable humanism, elaborate observation and subtle handling of characters and situations. The cinema of Satyajit Ray is a rare blend of intellect and emotions. He is controlled, precise, meticulous, and yet, evokes deep emotional response from the audience. His films depict a fine sensitivity without using melodrama or dramatic excesses. He evolved a cinematic style that is almost invisible. He strongly believed, "The best technique is the one that's not noticeable".

Ray directly controlled many aspects of filmmaking. He wrote all the screenplays of his films, many of which were based on his own stories. According to him, “I don’t mind taking a rest for three or four months, but I have to keep on making films for the sake of my crew, who just wait for the next film because they are not on a fixed salary.”

He designed the sets and costumes, operated the camera since Charulata (1964), he composed the music for all his films since 1961 and designed the publicity posters for his new releases. He trusted that, “The only solutions that are ever worth anything are the solutions that people find themselves.” He also said that, “The director is the only person who knows what the film is about.”

“When I write an original story, I write about people I know first-hand and situations I am familiar with. I don’t write stories about the nineteenth century.” In addition to filmmaking, Ray was a composer, a writer and a graphic designer. His interest in the western and European cultures is very vivid when he said, “At the age when Bengali youth almost inevitably writes poetry, I was listening to European Classical music.”

According to him, “If the theme is simple you can include a hundred details that create an illusion of actuality better.” He believed in “Dominus Omnium Magister. It means God is the master of all things.”

After the release of Agantuk, he felt, “I never believed that my films, especially Pather Panchali, would be seen throughout this country or other countries. The fact that they have is an indication that, if you are able to portray universal feelings, universal relations, emotions and characters, you can cross certain barriers and reach out to others, even non-Bengalis.”

“Somehow I feel that an ordinary person – the man in the street if you like – is a more challenging subject for exploration than people in the heroic mould. It is the half shades, the hardly audible notes that I want to capture and explore.”

বাংলায় পড়ুন

বাংলায় পড়ুন