What happens to your body in space? NASA’s Human Research Program has been unfolding answers for over a decade. Space is a dangerous, unfriendly place. Isolated from family and friends, exposed to radiation that could increase your lifetime risk for cancer, a diet high in freeze-dried food, required daily exercise to keep your muscles and bones from deteriorating, a carefully scripted high-tempo work schedule, and confinement with three co-workers picked to travel with you by your boss.

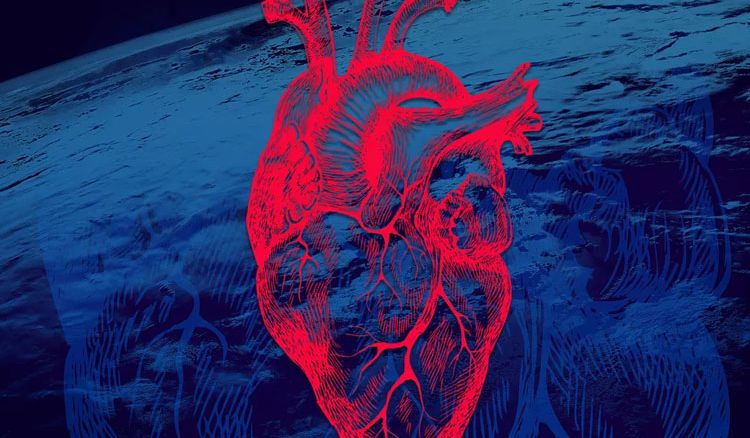

But what, exactly, happens to your body in space, and what are the risks? This study would focus on how space affects our most important blood-pumping organ, the heart. Space isn’t very kind to the heart. In fact, the heart actually undergoes a change in shape after being in microgravity for a long time. On Earth, the heart hangs in the chest and takes on a somewhat oblong shape because it’s constantly pulled down by gravity. But in space, in the absence of gravity the heart needs to adjusts. According to Michael Bungo, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Medical School who has studied the effects of spaceflight on the heart, the heart no longer hangs there, and becomes more spherical in nature. Additionally, on Earth, the heart is constantly working against gravity to pump blood up from the legs all the way to the head. Without gravity, the heart doesn’t have to do as much work to get the blood where it needs to go. And as a result, the heart can lose critical muscle mass.

Complicating matters further is the fact that astronauts in space lose blood volume, so the heart has less fluid to pump. That’s a side effect of microgravity, which causes fluids to shift in the body. Blood tends to collect more toward the lower extremities on Earth, since people spend most of their lives upright; the blood pressure in your veins is going to be higher in your feet than in your hips, for instance. Well in space, a lot of the blood that normally sits in the legs gets redistributed to the heart, and the body, once again, adjusts.

Less blood means the heart, once again, gets some slack. And that can be a problem for astronauts when they return to Earth. When thrust back into gravity, a person’s blood will rush to his or her feet. But low blood volume means there’s less blood to return to the upper part of the body — plus the heart is probably not as capable of pumping that blood. So astronauts run the risk of fainting when they get back to Earth, since they don’t have adequate blood flow right away to the head.

Fortunately, astronauts have strategies to combat these problems. Crews will often load up on fluids before they return to Earth to increase their blood volume and avoid fainting. Astronauts also have a strict daily exercise regimen to keep their hearts strong and healthy. And the good news is most of these changes are temporary: the cardiovascular system usually goes back to normal on Earth.

বাংলায় পড়ুন

বাংলায় পড়ুন